Anyone that’s ever tried this thing called life can attest to how difficult it often gets. Not only do you have to literally survive —unfortunately still a struggle for many even after 6 thousand years of civilisation — you also have to deal with this sticky yet elusive goop called morality.

The question of how we should live is as ubiquitous as the air we breathe, yet there’s no agreement as to its answer. Perhaps you should do what god tells you, but then which god do you pick? Perhaps you should chase money and power, but then what about interpersonal relationships? Perhaps you should focus on maximising happiness for all, but what about your own happiness?

Attempting to put an end to all this agonising, Aristotle proposed a moral framework called virtue ethics. The framework takes a rather unique approach to ethics, even in comparison to the works of modern moral philosophers. Virtue ethics places moral value on the individual character. That is, to be a good person is to be a person with good characteristics.

This stands in contrast to more popular moral frameworks that often place moral value on actions or their outcomes. That is, to be a good person is to do good things. These frameworks have their own set of problems, and although I won’t be explaining exactly how in this article, Aristotle sidesteps them completely by focussing on character before action.

Alright, so virtue ethics is about having good characteristics, but what exactly makes a good characteristic? Some may think brutal honesty is good, while others would say deception to prevent harm is better. Aristotle solves this by calling on an idea humanity has held sacred for millennia: balance.

A good characteristic is one that balances between two extremes. For example, when it comes to confidence, the one extreme is rashness — charging into battle without any armour — and the other is cowardice — not facing your fears. A good balance between these two is what one would call courage.

This is how Aristotle defines virtue — balancing between extremes, namely vices. This notion is called the doctrine of the mean, and full disclosure it isn’t without its fair share of critiques from moral philosophers. But suffice to say it doesn’t have any more than the other frameworks out there.

One of its major critiques is that it doesn’t actually tell you how to make a real-life moral decision. For instance, when deciding whether or not to tell your bipolar boyfriend you cheated on him, it isn’t clear what the virtuous thing to do is. You’re either harmfully honest, or harmfully deceptive. And this is only one of a million moral dilemmas that has you caught between two vice-ful actions.

While many see this as a defeating blow to virtue ethics, I beg to differ. I cannot guarantee even Aristotle will agree with me, but I believe my response to this problem saves virtue ethics, and subsequently serves as a good guide to living life.

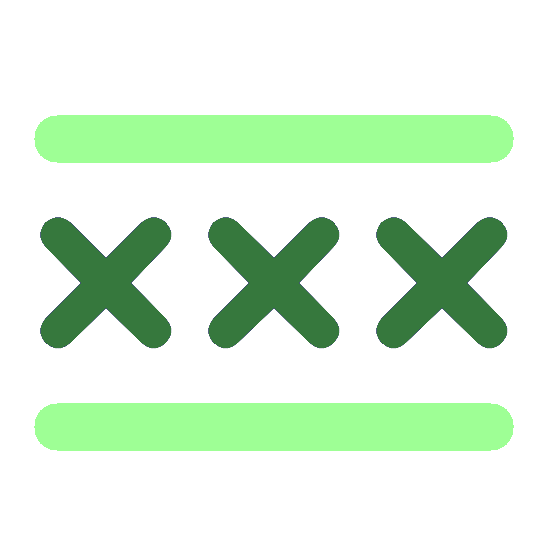

While the original virtue ethics proposes one should be virtuous in every action they execute, I propose that what’s more important is that which originally inspired Aristotle: balance. See virtue as a life-long balance, as opposed to a per-action basis. So don’t worry about being perfectly courageous all the time. Just make sure you live a courageous life. See this illustration of life-long virtue.

The idea I want to highlight with this illustration is that being a good person takes doing a lot of things, making a lot of mistakes, and learning from them. The more you live, the better you’ll get at balancing character and the more virtuous you’ll be able to be.

To further illustrate these ideas, I’ve written up a list of example virtues with their extremities (vices). Aristotle did name some cardinal virtues he believed are sufficient for being good, but I think the true list of good characteristics is endless.

- cowardice — courage — rashness

- insensibility — temperance — indulgence

- shamelessness — modesty — bashfulness

- surliness — friendliness — ingratiation

- subservience — dignity — stiff-neckedness

- mean-spiritedness — magnificence — ostentation

- naivety — practical wisdom — unscrupulousness

- dullness — good-humouredness — buffoonery

- stinginess — generosity — spendthrift

- deception — tactfulness — brutal honesty

Image credit: Yulong Lli